|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

Thread Tools | Search this Thread | Display Modes |

|

|

#1 | |

|

Member

Join Date: Mar 2007

Posts: 65

|

Dao (sword)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Quote:

Yanmao Dao Goose Quill Sabre What are your thoughts ? I think that the etymology of the term needs to be looked into . Sinitic and Tibeto-Burman are thought to share the same stem : Tai -Kadai has similarities to Sinitic postulated as being due predominantly to the loaning effect of close proximity. Dha in Bama ( Burmese ) simply means blade or knife and this seems to be shared with the basic Chinese term according to the article above . Interestingly the fighting sabres used in Burma also have terminology relating to animal forms . I only know of one but I am told there are others : Hnget Tchi Daung Dha - means Stork ( large bird ) Quill Dha and refers to the pointed fighting sword with a short hilt and a slight taper towards the ferrule. It would be interesting to know what the term Dao used by the Kachin and Naga actually mean and whether the Thai ( Siamese ) term actually has a root meaning or means "foreign blade" ( with krabi being the correct term for sabre / knife / blade ) . As far as I'm aware the Tai ( Shan ) in Burma also call it Dha ( albeit with a slightly different tone ) : I do not know what the Tai word for knife is but could find out on my next trip back to Burma . I am also interested in the weaponary used by Tai-Kadai in China ( Dai , Tai Lue , Zhuang etc ) and the Khamti in Assam if anyone knows on this forum and similarly whether traditional Bai or Yi ( in Yunnan ) weapons are different from the Chinese forms. Last edited by ~Alaung_Hpaya~; 3rd April 2007 at 12:45 PM. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

#2 |

|

Member

Join Date: Dec 2004

Posts: 987

|

It is tempting to draw an etymological link between the Chinese 'dao,' the Tai 'dahb/daab' and the Bama 'dha,' and even the Kachin 'dao.' They all seem to mean more-or-less the same thing, which is basically 'blade,' or 'curved blade.' A problem, or rather obstacle, that I have in addressing that question is not knowing the actual intonation of the various words. My Western ear would have a hard time with the subtlies, as well.

While I think it very likely that the dha/dahb in some form came from Yunnan (specifically Nan Zhao), I don't see a strong connection with the Chinese dao in its various forms. Not only are details such as the handle shape and presence of a guard different, the balance is quite different as well, the dao having a POB farther out along the blade than the typical dha, and much farther out than that of the typical dahb. Dao also lack the graceful curve of the dha and dahb. Where the influence is most clearly seen (not surprisingly) is in Vietnam, where Chinese influence was strongest. Even there, however, one sees two distinct types of sabre, one clearly a variation of the dao (even called "dao"), and the other seemingly more closely related to the dahb ("dai dao"). It is interesting (at least for non-linguist me) to speculate whether the "dai dao" is a "Tai dao," from the point of view of the Vietnamese. IN any event, it is found in southern Vietnam (Cochin) rather than northern Vietnam (Tonkin). Cochin was historically more linked to the rest of SEA than Tonkin, which at one point was actually a Chinese province. There is also a Vietnamese version of the jian (the kiem), which is not seen at all in other parts of continental SEA. My expectation would be to see both dao-related and jian-related swords if there were a Chinese influence, as one sees in Vietnam. The absence of the jian style says to me that Chinese, by which I mean Han Chinese, influence in most of continental SEA was limited. I have not yet found any clear evidence of what a Yunnan/Nan Zhao style dao might look like, though I have seen a few dha provenanced from Yunnan that resemble a certain style of Shan dha, with their own decorative details. |

|

|

|

|

|

#3 | |

|

Member

Join Date: Dec 2004

Posts: 987

|

Quote:

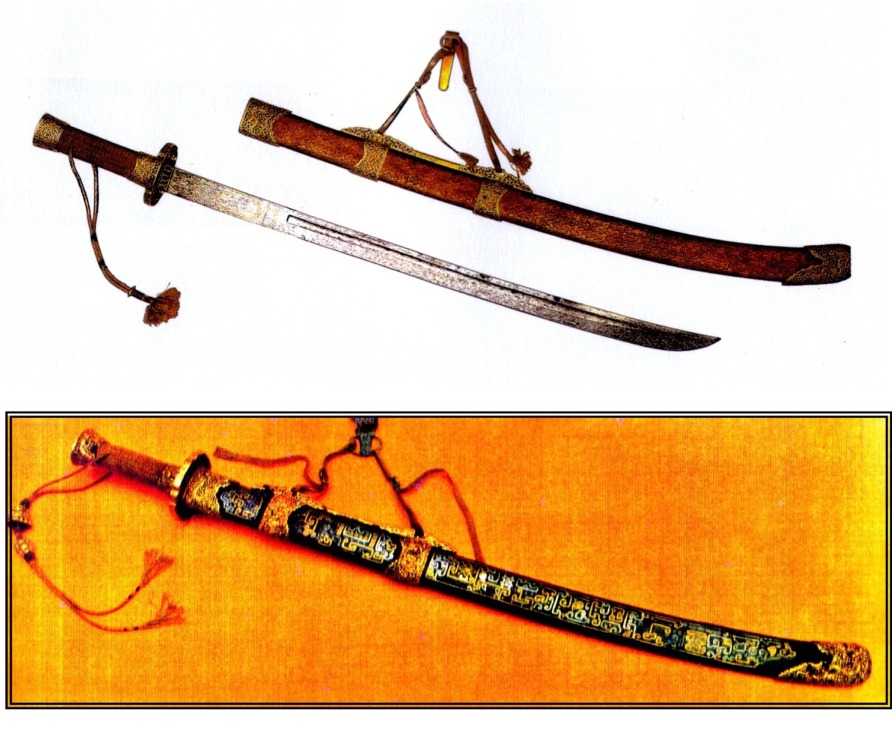

The grip on this one looks like what you are describing, but the blade tip is not upswept:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

#4 |

|

Member

Join Date: Mar 2007

Posts: 65

|

Thanks Mark

I'm wondering about common origin I guess rather than actual derivation from Dao post Tang dynasty ( 618 - 907 AD ) or even Song . It certainly would be of interest to me if anyone can ( literally ) dig up swords from Nan Zhao . |

|

|

|

|

|

#5 | |

|

Member

Join Date: Mar 2007

Posts: 65

|

Quote:

I'm talking about about the first one and about the blade not the grip . Sorry I'm still getting my head around the terminology . I meant the width of the blade narrows as it approaches the flared ferrule ( which acts abit I guess like like a false tsuba ) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

#6 | |

|

Member

Join Date: Dec 2004

Posts: 987

|

Quote:

The one book on the art of Nan Zhao that I have found does not show any weapons.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|