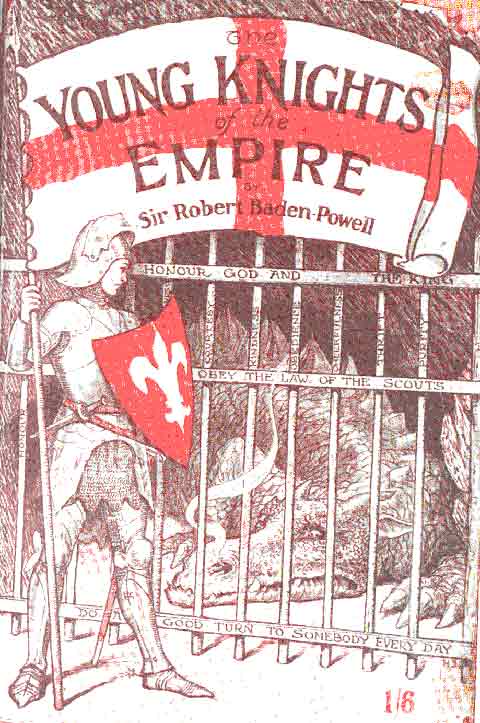

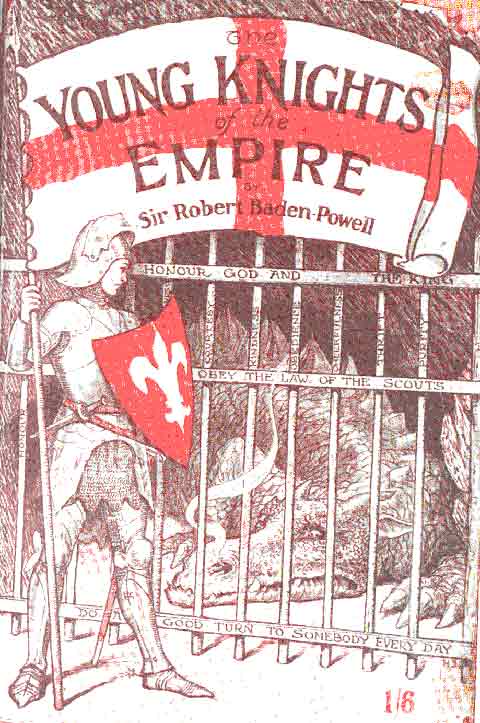

Figure 6.1: Cover of Baden-Powell's 1916 Young Knights of the Empire.

Students of Arms; a survey of arms and armour study in Great Britain from the eighteenth century to the first World War.

by Michael Lacy

Chapter 6:

Arms and Armour Study in Edwardian Britain

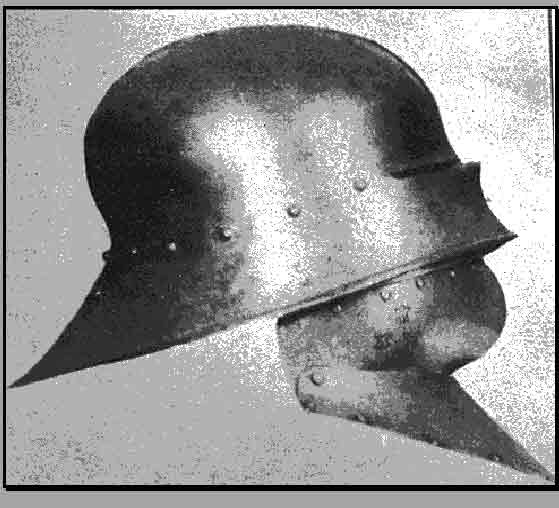

The public fascination with the middle ages continued into Edwardian age on many levels. The legacy of the Gothic Revival was so deeply ingrained in British society that many forms of medievalism had become part of the national character, from the gothic architecture exemplified by the Houses of Parliament to the chivalric code of conduct of the British gentleman. The image of the knight in shining armour, particularly Saint George, was increasingly used as a symbol of the Empire and was to be seen in monument, posters and books extolling discipline and martial virtue (figure 6.1)[1]. More dramatic expressions of medievalism were also available, such as the tournament held at the Empress Hall at Earl’s Court on 11 July 1912. Described as a ‘revived Eglinton tournament,’ four of the six knights who jousted before an audience which included Queen Alexandra, Lord Curzon, Lord Rosebery, Winston Churchill and Pierpont Morgan were descended from participants in the tournament of 1839 and one, the Earl of Craven, was even wearing the armour that his grandfather had borne at the lists 73 years previous [2]. Both Lord Curzon and Pierpont Morgan were themselves armour collectors, and the trade in antique arms and armour was becoming increasingly competitive as wealthy American millionaires entered the market.

Medieval and renaissance armours were increasingly viewed as works of art by many collectors and writers of the time. As mentioned in the preceding section, published articles dealing with medieval arms and armour began to appear with increasing frequency in art journals after the turn of the century, while the more traditional antiquarian publications such as the Archaeological Journal and Archaeologia were more given over to topics that were more strictly concerned with archaeology in the modern sense of the word (Graph 4). Publications such as The Connoisseur, the Art Journal, the Burlington Magazine , Apollo, the Magazine of Art and Country Life became important conduits for new publications in arms and armour study in the early decades of the twentieth century. Between the years 1900 and 1920, no less than 93 articles on topics dealing with arms and armour appeared in the pages of The Connoisseur.[3] By comparison, only 17 such articles appeared in the Archaeological Journal during this time, and none at all in the Journal of the British Archaeological Association.

During the early decades of the twentieth century, the long association between arms and armour study and the antiquarian and archaeological societies was at a low ebb. Indeed, between 1895 and 1910 a single writer, Lord Dillon, was responsible for all of the articles relating to arms and armour that appeared in the Archaeological Journal and one of the two such essays printed in Archaeologia. During this time, all of the other writers seem to have abandoned the more venerable journals so long identified with arms and armour study and submitted instead to the art journals. Although this change may reflect editorial decisions by the more traditional journals to place a greater emphasis on the findings of field archaeology, it is more likely a result of the social habits of the armour collecting fraternity. Edwardian collectors were men of wealth, leisure and taste, but they were also men of society who perhaps felt more akin to collectors of objets d’art than they did to the much-lampooned antiquary or the dusty archaeologist. As the ranks of armour collectors included a number of historical genre painters, as mentioned in the previous section, it seem only natural that groups such as the Kernoozers would serve to disseminate a greater appreciation for the arts amongst arms and armour societies.

Another factor which influenced the shift from archaeology to art was the fact that many of the finest armours, particularly those of the renaissance, had been researched to the point where a definite provenance could be established and even, in some cases, the name of the smith who had originally produced them. Works such as Boehim’s Meister der Waffenschmiedekunst had identified the armourer’s marks of hundreds of armour and weapon manufacturers, and details of form, style and decoration allowed the experienced connoisseur to make sound judgements as to the origin of those pieces which were not so marked. Just as a painting’s value will rise if it can be attributed to a famous artist, so it became (and remains) with armour; a fine embossed shield would probably catch the eye of an arms connoisseur at an auction, but an embossed shield by Francesco Negroli could well spark a bidding war. Thus the ‘cult of secular relics’ was expanded to include not just the names of famous owners of weapons and armour, but also the names of the craftsmen who created them. Names of great medieval armourers such as Lorenz Helmschmied, Anton Peffenhauser and Tommaso Missaglia were to become well known in auction houses as wealthy collectors sought out the choicest pieces for their collections.[4]

The view of medieval arms and armour as objects of applied, or even fine, art was further reinforced with the opening of the Wallace Collection to the public in 1900, where many of the finest suits of armour that once graced the halls of Goodrich Court were displayed alongside the superb collection of sculpture, furniture, paintings and other works of art collected by Sir Richard Wallace whilst living in Paris. The opening of the Wallace Collection at the turn of the century provided London with two world-class collections of arms and armour available to the public, the other being the Royal Armouries at the Tower of London. Both of these collections were to become focal points for scholarly talent and research into arms and armour. After Lord Dillon, the Tower was home to a number of influential writers including Charles Ffoulkes, James Mann and Vesey Norman, while the name most associated with the Wallace Collection’s arms and armour is that of Sir Guy Francis Laking.

Sir Guy Francis Laking (1875-1919), a protégé of de Cosson, was the author of the last ‘grand scale’ general study of medieval arms and armour, the five volume Record of European Armour an Arms, published posthumously in 1921. Although this work did not contribute as greatly to the scholarship on the subject as did Hewitt’s Ancient Armour, it did present a comprehensive summary of current research, and its hundreds of photographs gathered from collections across Europe and America made it an important reference volume for collectors and students alike. A man of great energy and enthusiasm Laking produced in his short life authoritative catalogues of the armour collections of Windsor Castle, the Armoury of the Knights of St. John at Malta, the Wallace Collection as well as several private collections. A distinguished connoisseur of art as well as of arms and armour, he held many official posts including that of the Keeper of the King's Armouries at Windsor, The Inspector of the Armoury at the Wallace Collection and the Keeper of the London Museum (which he to a great extent created). Through his friendship with King Edward VII, he was able to combine his official posts with a long career in the antiquities market as an art advisor for Christie’s auction house, a situation unthinkable today.

Guy Francis was the son of Sir Francis Laking, Bart, and Beatrice, daughter of Charles Barker.[5] Sir Francis Laking was the family physician and friend of Queen Victoria, Edward VII and George V, and ‘a regular guest at Windsor, Balmoral and Sandringham.[6]’ Brought up in the shadow of Royalty, young Guy was to become an accomplished courtier, and a close friend of both King Edward VII and his successor. His education at Westminster school ended abruptly when he was but fifteen years of age after ‘a boyish escapade with a pony he had bought, and leave that was taken the French fashion,’ and he studied Architectural Drawing for a time before his passion for art and antiquities brought him to the attention of Mr. T. H. Woods, a partner at Christie’s, who invited the young man to join the staff.[7] Christie’s auction house was near Laking’s home in Pall Mall, and he was a frequent visitor to the premises where he studied and admired the armour and works of art that were displayed there prior to auction. Laking’s interest in armour blossomed early; it is recorded by Hayward that he wrote an essay entitled ‘The Sword of Joan of Arc’ when he was only ten.[8] In 1891, he sought an introduction to Baron de Cosson, who was visiting London at the time. De Cosson recalls their first meeting in the introduction he wrote for Laking’s Record in 1919;

‘I well remember how, some twenty-eight years ago, being in the shop of a well known armour dealer, I was told that young Laking, the son of the Physician to the Prince of Wales, was anxious to know me and had been trying to effect a meeting with me. A few weeks elapsed and this meeting took place and I saw a slim boy of about fifteen who, with a hurried, impetuous, cracked voice, launched into all sorts of questions concerning armour and arms. His ardent enthusiasm pleased me greatly, and, as long as I stayed in London, we saw much of one another and indulged in endless disquisitions on the subject of arms, and these discussions have been continued at intervals ever since.’[9]

Laking’s first published work for Christie’s was the sale catalogue of the Zschille Collection, which was sold in January 1897. This was the first of many catalogues which Laking authored in his capacity as Art Adviser to the famous firm of auctioneers, a post he held throughout his life. Laking’s passion for the subject served him well in his profession, and his catalogues were highly praised by students and collectors of armour. ‘In the catalogues he prepared for Christie’s,’ writes Hayward, ‘Laking described the objects offered for sale with a combination of scholarship and enthusiasm which was far removed from the dry and uninspired commentary of the conventional catalogue.’[10] ‘His catalogues were growing to be more and more authorities for reference;’ adds Cripps-Day, ‘in his hands they ceased to be merely lists of names and numbers.’[11] Laking’s expertise was not confined to arms and armour, as Hayward relates;

‘He became well-known for his knowledge not only of arms and armour but also on medieval and Renaissance works of art, on French furniture and Sèvers porcelain. His opinion is said to have been widely sought on paintings as well. Such was his ability in recognising works of art that he was already sufficiently qualified to express an expert opinion on many kinds of works of art at an age when most men are entering their profession.’[12]

During the 1890’s Laking enjoyed life as a popular member of London society. ‘A favourite companion at the Marlborough Club and elsewhere of the Prince of Wales, the future Edward VII,’ writes Sheppard, ‘for whom his "inexhaustible fund of scandalous anecdotes about the medieval nobility’ had a great appeal...like his royal patron he is widely reputed ‘to have indulged to the full in the escapades associated with the Naughty Nineties.’[13] In 1898 Laking married Beatrice Ida Barker and lived in rooms in Ambassadors’ Court within St. James Palace, described by one newspaper as one of ‘the most covetable homes in London.’[14] Laking’s temperament was more suited to the reign of his patron, who succeeded to the throne in 1901, than to the more sombre reign of Victoria. The cigar-smoking Edward VII had a zest for life and society and enough human foibles to allow him to enjoy both to the full, and he very much set the tone for what has become known as the Edwardian era.[15] Laking, a handsome and charming man with all the right social connections, was very much in his element in the early years of the twentieth century.

Yet Laking was not simply a fashionable Edwardian dandy, for during this time he had been hard at work at Christie’s. His reputation as an expert in the field was such that in 1899 he was invited by the Trustees of the Wallace collection to catalogue the arms and armour at Hertford House. Laking produced the first catalogue of this collection in 1900, timed to coincide with the official opening of the museum.[16] His work at Hertford House was recounted in the pages of The World in 1907;

‘His opportunity of putting his acquirements to the test came when the great Wallace collection became the property of the nation. The wonderful treasures of Hertford House were in a state of almost hopeless chaos. It was a question of reducing them to order, and in view of the approach of the opening day, against time. Lord Redesdale suggested the name of Guy Laking as that of one of the few men equipped with sufficiently catholic qualifications for the task. He accepted the work with misgivings, because time was short. By working all day at Christie’s, and nearly all night at Hertford House, for two feverish months Mr. Laking produced his splendid catalogue raisonné, the arrangement of the collection as it is to-day, in time for the opening ceremony by the Prince of Wales.’[17]

Laking’s arrangement of the collection was, like Meyrick’s work at Windsor, more decorative than instructive, with much of the collection being displayed in decorative panoplies along the walls (plate 6-I). Laking explains in the foreword to the catalogue why the decision was made to display the collection in this manner;

‘In the present arrangement of the collection of armour and arms at Hertford House, the Trustees, with forethought, have considered it best that chronological order should, to a great extent, give way to the method employed by the late Sir Richard Wallace in his disposal of the collection, that is, the even grouping over the walls of the galleries of various panoplies of arms and armour, but with the present difference that the richer and more perishable examples are enclosed in glass cases...When the collection was formed, it was to demonstrate the beauty of the armourer’s art of nearly all periods and nationalities, and with no idea of illustrating the various forms and fashions employed in armament offensive and defensive.’[18]

Laking’s work at the Wallace Collection was considered a great success and in 1902 he was appointed by King Edward VII as Keeper of the King’s Armoury, a post specially created for him by the monarch, and set to work on re-organising and cataloguing the Windsor collections of armour, furniture and porcelain. There he worked alongside Sir Lionel Cust, Surveyor of the King’s Pictures, Gentleman Usher and friend of King Edward and his court who wrote of this time;

‘My warrant of appointment named me Surveyor of the King’s Pictures and Works of Art, in the latter category being included China, Sculpture, Bronzes, Tapestry, ornamental furniture and anything which could be called a work of art. It fortunately did not include armour, about which I knew very little, because the King created the post Keeper of the King’s Armoury, which he conferred on Mr. Guy Laking, son of his Chief Medical Attendant, Sir Francis Laking, Bart. Guy Laking was already a noted authority on armour, and, as an assistant in the great auction firm of Christie’s, he had an extensive acquaintance with works of art of every description, which made him a most valuable colleague. Indeed, Laking and I worked like brothers together in the overhauling and reconstitution of the royal collections.’[19]

Laking’s duties at Windsor included acting as a host and ‘tour guide’ to the castle’s treasures to important visitors, as when he, Lord Esher and Sir Lionel received Prince and Princess Arisugawa of Japan and conducted them around the Castle in 1902.[20] Laking’s expertise in armour and art was called upon by King Edward, who desired ‘a series of books dealing with his collections of Works of Art, handsomely got up in themselves, such as he could offer to his relatives and his guests in accordance with the high dignity of the Throne,’ writes Cust, ‘To Guy Laking he entrusted the making of the three great books on the Armoury, the Furniture, and the Sèvres China at Windsor Castle.’[21] The published products of his labours at Windsor were The Armoury of Windsor Castle in 1904, followed by The Furniture of Windsor Castle in 1905 and the Sèvres Porcelain of Buckingham Palace in 1907. Laking also managed to find the time to accept an invitation from the Governor of Malta to re-arrange the armoury of the Knights of Saint John at Valetta, where he also catalogued the collection and undertook a considerable amount of research in the archives of the Order of St. John. The result of this research appeared in The Armoury of the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem, Malta in 1903.[22] During this time Laking was also collecting material for a major treatise on arms and armour, as well as producing a stream of articles and essays for various art journals. He published a six part essay in the Art Journal entitled ‘The European Armour and Arms of the Wallace Collection ’ in 1902-3, two papers in the Connoisseur, ‘Armour of Sir Christopher Hatton: the Dymoke suit,’ in 1902, and ‘Mr. Edward Barry's collection of arms and armour at Ockwells manor, Bray,’ in 1905, as well as additional articles for The Ancestor and the Art Journal.

In 1908 Laking returned to the Wallace Collection, where he was appointed Inspector of the Armouries at Hertford House, and began a reorganisation of the collection on a more chronological basis, removing the decorative panoplies from the walls and installing the items in racks and cases.[23] A third edition of the catalogue was issued in 1909, closely followed by the fourth in 1910.[24] Although Laking was disappointed in that he had failed to get the appointment as Keeper of the Wallace Collection, a post he had dearly wanted and which had instead gone to D. S. MacColl, his spirits were soon lifted when in 1911 he was appointed the Keeper and Secretary to the Trustees of the London Museum, thanks to the patronage of Lord Esher.[25] This was Laking’s most challenging post, as he was not so much a curator, but a creator, of a new museum that had neither a collection or a permanent home to house it in. He had to collect, catalogue and arrange the material, while at the same time meeting his many other obligations. Laking set to the task with his usual energy, as described in detail by Sheppard in his history of the London Museum, The Treasures of London’s Past. ‘With Harcourt, Esher and Waechter, Guy Laking was one of the four cornerstones of the London Museum,’ he writes, ‘He was the first and some may think the greatest keeper of the London Museum.’[26] Through his hard work the museum, announced on 25 March 1911, was to open its doors almost exactly three years later at Lancaster House on 23 March 1914. During this time Laking had almost single-handedly seen to the creation of the museum’s collection of exhibits, laid the foundations for the museum’s curatorial staff, catalogued and numbered the items and secured funding for the new museum.[27] During this time he still found time to gather material for his great treatise on medieval armour and weapons. ‘The work,’ writes Ffolkes, ‘was of such portentous and alarming proportions, and its ultimate publication and completion so problematical, that among his intimate friends it was known as "When?"[28]

Throughout Laking’s career, he was a member of the close-knit community of dealers, collectors and researchers of arms and armour. In addition to his close friendship with the Baron de Cosson, Laking was on good terms with most of the other writers of the time including Viscount Dillon and Charles Ffoulkes, Dillon’s successor at the Tower. Laking and Ffoulkes met in 1913 and were able to effect some beneficial changes to collections of Windsor and the Tower by virtue of their positions as custodians of these two important armouries. ‘Laking suggested to King George V that some valuable pieces of armour used as decoration at Windsor be returned to the Tower in exchange for pieces of less historic value,’ writes Parsons, ‘and on 23 July 1914 portions of armour of Henry VIII, Sir John Smythe and William Somerset were reunited with their original suits in the Tower.’[29] In 1915 Laking did Ffoulkes a good turn that the latter recalled in Arms and the Tower. Ffoulkes had planned to issue an up-to-date inventory and catalogue of the arms and armour in the Tower collections, but the officials at the Stationary Office balked at the cost of production. Laking, upon learning of this, promptly ordered one hundred of the yet-to-be-printed catalogues which convinced the authorities that the demand would sufficient to cover the costs.[30] Ffoulkes never forgot this act of kindness.

Although Laking was unable, due to his professional involvement at Christie’s, to become a member of the Kernoozer’s Club, he was one of the leading members of the previously mentioned Meyrick Society, originally called the ‘Junior Kernoozers.’ Laking was vice-president of the society when he treated its members to a lavish banquet at his home near Regent’s Park which he styled ‘Meyrick Lodge,’ having moved from St. James’ Palace in 1911.[31] The feast of roast peacock, which is still spoken of in awe in armour collector’s circles, was attended by 40 guests drawn from the membership of the Meyrick Society and from Laking’s circle of friends which included many of the most respected writers and collectors of arms and armour of the early twentieth century, including Sir Hercules Read, the president of the Society of Antiquaries; Sir E. Barry, Bt., Sir George Frampton, R.A., Sir Francis Laking (father of the host), Charles Ffoulkes (then Keeper of the Armour in the Tower), Theo. McKenna, Mr. A Forestier, Mr. Clifford Smith (Keeper of the Mediaeval Furniture in the Victoria and Albert Museum), J. G. Taylor, and Cripps-Day.’[32] James Mann, writing in 1940, tells of Laking’s time in the Meyrick Society;

‘For many years the late Sir Guy Laking, the first Curator of the London Museum and the King’s Armourer, was the life and soul of the Meyrick Society. He inspired all around him with his intense enthusiasm for fine armour and arms, and his lavish entertainments are still spoken of with awe by the older members...At meetings held in his home at Oxford Square, and later at Avenue Road, where he renamed his House Meyrick Lodge, members were always sure of finding some new and splendid acquisition to admire.’[33]

During the feast, in a display typical of Laking’s flamboyance, his young son, dressed as a page, and Miss Hilda Green, his governess, passed an antique loving-cup around the seated company. The young boy wore a heraldic tabard while Miss Green appeared as Joan of Arc ‘dressed in a suit of armour made specially for the distinguished French sculptor who modelled the famous figure of Joan of Arc in Paris.’[34] Ffoulkes recalls the event, the timing of which may possibly have been due to the publication of his new Tower catalogue, which Laking had helped to make possible with his generous purchase;

Figure 6.3: Miss Hilda Green. The governess of Laking's children as she appeared at Laking's famed 'Peacock feast,' dressed as Joan of Arc.

‘Eventually the work, with its Royal dedication, was completed, and the first volumes were presented to His Majesty on 14th June 1917. The day of publication Laking asked me to dine with him, and to my amazement I found a quasi-medieval banquet at which his children’s governess, equipped in full armour, carried round the loving-cup to the guests, on whose plates reposed a copy of my catalogue tied up in gold brocade.’[35]

In 1914, Guy Laking succeeded to his father’s baronetcy, and in June of that same year was made a Companion of the Order of the Bath. ‘Harcourt had of course arranged this, as Laking knew perfectly well,’ writes Sheppard, ‘just as he knew that Harcourt had arranged a baronetcy for Sir Harry Waechter. But this in no way diminished the value which Sir Guy placed upon his CB. After all, he had not bought it, and he had not inherited it; he had been given it just for sheer personal merit.’[36] The same year saw the release of the catalogue of the oriental arms in the Wallace Collection, which Laking had found time to complete in spite of his constant work at the new London Museum which was scheduled to open in March of that year.[37] Despite these good turns of fortune, the outbreak of the First World War caused the Museum to close its doors early in 1916, and Sir Guy’s health began a slow and steady decline, as Sheppard recounts;

‘Laking seems for reasons of health to have spent much of the war years in the country. His museum correspondence shows that between 1911 and 1914 he had frequently been ill (or ‘seedy’ as he called it), severe bronchitis being the main trouble. Soon after the opening of the museum at Kensington Palace in March 1912 he had had ‘a severe illness, which necessitated his laying up for some weeks’. In November 1914 he was living in his ‘country’ house, York Gate, Broadstairs, and later he was for a while at Wargrave, near Henley. In the summer of 1915 he stayed with Lewis Harcourt at Nuneham Park, where he proved to be ‘a dreadful duffer at cards’, and in the autumn he was at Barton Manor in the Isle of Wight, where he rearranged the royal museum at Osborne.’[38]

By the spring of 1918, he had been ordered by his doctors to spend at least three months resting, as they feared he was suffering from heart disease. ‘For a while there was some improvement,’ writes Sheppard, ‘but in November he was "seriously ill with pneumonia, following influenza and heart trouble," and was going to be away for "some considerable time." ..By mid-November, when Queen Alexandra sent a telegram of inquiry, he was slipping away, and he died on 22 November 1919 at his London home at Meyrick Lodge, Avenue Road, Aged only forty-four...’[39] Laking retained his love for armour to the last, and Mann spoke of how, on his death-bed, Laking asked for his latest armour acquisition to be brought to him that he might gaze upon it one final time.[40] He was buried at Highgate Cemetery, his funeral at St. James’s Palace attended by representatives of King George and Queen Alexandra and many of his friends and associates. Laking was survived by his widow, young son and daughter all of whom, sadly, died within a few years.[41] Laking’s fine collection of arms and armour was sold at Christie’s in 1920, and fetched £34,000 - a very considerable sum for a collection which consisted of only 299 lots and which included no full harnesses of armour. This was due, writes Hayward, to the fact that there was very stiff competition at the auction from American buyers.[42]

Laking was remembered by his friends as a charming and energetic man, and one who was also known for his kindness. ‘I was once told that is was said of Laking that he would always find something kind to say about a fellow collector’s object,’ writes Blair, ‘however humble it or its owner was.’[43] In his short life, he accomplished much both in his capacity as an administrator and as a writer on arms and armour. He produced catalogues of several of the most important collections in the British Empire, including those of the Wallace Collection, Windsor, and the Knights of St. John in Malta, a number of articles in art journals such as Connoisseur, and he had prepared for publication a massive five volume treatise on arms and armour that was to be published posthumously in 1920-1921. In his private life, however, Laking often strayed from his image of a hard-working and honest gentleman. Laking’s marital infidelity was the subject of much gossip - he was reputed to have a string of mistresses that included the ‘Joan of Arc’ who served his guests at his famous peacock feast.[44] The Baron de Cosson, who had known Laking since the latter was a teenager, may have been making an sly reference to his young protégé’s reputation when he wrote the following comment in the introduction to Laking’s Record of European Armour in 1919;

‘[Archduke Ferdinand, Count of the Tyrol] also, and I think greatly to his credit, set an example often followed since in the House of Hapsburg, and married a lady, not a princess, said to be the most beautiful woman of her time, and from a pretty long experience of collectors, I should say that he was not the only man who has combined a taste for beautiful arms with a love for fair women.’[45]

Laking had a very expensive life style, one friend commenting that he ‘spent money like one who has a store of gold angels and gold nobles in an iron chest rather than as one who draws cheques on a bank account.’[46] However he did not, as Blair notes, have a great private wealth to draw upon nor, according to Sheppard, did any of his many official appointments carry a salary.[47] His source of income was through his work as an art adviser and, presumably, through commissions on sales. Laking’s position was thus one in which conflicts of interest were bound to arise, and as Blair notes, ‘there is evidence to suggest that he was not always entirely scrupulous about his methods.’[48] Blair elaborates in his 1992 contribution to Watkins’ Studies in European Arms and Armour;

‘A man of immense charm and, it should be mentioned, also of genuine kindness, he was an extremely attractive personality, especially to women. Because of these qualities, and probably also because of his royal connections, he had many wealthy friends, whom, according to Mann, he persuaded to collect arms and armour on the sale of which he would undoubtedly have received a commission from the dealers concerned. Two collections formed with Laking’s assistance by wealth people with no knowledge of arms and armour, Lord Astor of Hever and Alice de Rothschild of Waddersdon Manor, contain a high proportion of fakes of a kind that could not possibly have deceived him, and it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that he was party to the deceptions and financially rewarded for them.’[49]

Laking’s lavish lifestyle may have occasionally placed him in financially awkward circumstances, contributing to the temptation to profit from the trust which his friends and clients placed in his professional opinion. Fraudulent suppliers and dealers could also use such occasions to force his hand. James Duveen writes of a scandalous account of a fraudulent armour sale in a chapter of Secrets of an Art Dealer entitled ‘The Blackmailing of an Expert,’ which rings all too true. Duveen begins his story;

‘In 1905 there was in London a very brilliant and debonair young man who was an acknowledged authority on art and, in particular, on old armour. He was, of course, in close touch with all the big dealers and buyers in London and the United States, and it is in this connection that he was drawn into one of the biggest ‘ramps’ of the century. Charming in manner and good-looking, he was an even greater expert on feminine beauty and vintage wine. It was commonly said that women could never say "No" to him. This was then an even more expensive game than it is to-day. However, by one shift and another, he managed very well until he became mixed up in a rather unsavoury affair which ended in his being heavily blackmailed.’[50]

‘Hugh Melmett,’ the story goes, was desperate for money to repay a debt owed to some unsavoury characters, and begs a colleague in the art world for assistance. His colleague, described as ‘one of the rising dictators of the art world’, is given the pseudonym George. ‘George,’ knowing that ‘Hugh’ is one of the most respected authorities of arms and armour - and desperate for money - offers him a Faustian pact by which he will deliver him from his creditors in exchange for a dishonest appraisal of two armours that had been ‘restored’ by the addition of false gold inlay - raising their value from £800 to £20,000. The target of this swindle was a wealthy New York collector given the pseudonym ‘Patrick P. Bordeaux’ in the story.[51] Blair is almost certainly correct in identifying the anonymous dealer in Duveen’s story as Guy Laking, particularly as Duveen goes on to note that ‘Hugh’ died tragically at an early age.[52] Despite his great energy, charm and kindness, Laking’s weakness in the face of temptation was a serious flaw in his character. Blair recalls a conversation he had with Sir James Mann, who succeeded Ffoulkes at the Tower of London, in which Laking’s death was mentioned. ‘I remarked to him that it was sad that Laking had died so young. His reply,’ writes Blair, ‘which I had always remembered because it astonished me, was that perhaps it was not so sad, because had Laking lived much longer, he would not have had any friends left!’[53]

Laking did not live to see the publication of his magnum opus, the five volume Record of European Armour. ‘Sir Guy Laking died on the 22nd of November 1919,’ writes Cripps-Day, ‘a few days after his publishers had been able to send him the first volume of His European Armour and Arms.’[54] After his death the manuscript of the remaining four volumes, together with notes and his vast collection of photographs that he had solicited from collections around the world were taken up by Francis H. Cripps-Day, a noted authority on arms and armour himself, who undertook the task of seeing the Record to completion from 1920-1921.[55] In his own work, the Record of Armour Sales, Cripps-Day pays tribute to Laking, writing ‘Notwithstanding the vast amount of work which the various posts he occupied entailed, he found time to prepare the very large and important book on armour and arms...which will crown the achievements of his brilliant but all too short career as a student of arms.’[56] Laking stated his objectives in writing the Record in the preface to the first volume of the work, in which he concisely and modestly spells out the strengths and weaknesses of his approach;

Figure 6.4: Advertisement for Laking's Record of European Armour and Arms in the Connoisseur, February 1920.

‘This book does not pretend to open up a new road to the student of arms and armour...My evidence confirms the accepted theories of the great scholars who preceded me. Herein I trust lies its interest and value to the reader. I feel, therefore, that my homage is first due to the memory of Sir Samuel Rush Meyrick, that pioneer of all who have been learned in the study of the harness of war, and after him I think gratefully of those who followed in his footsteps. My book owes much to their research, although of necessity it covers a wider field, in view of the work of archaeologists during the last forty years. At least I may claim for my pictures that they are all drawings or photographs of genuine pieces. I say frankly that my long experience in handling the work of the old armourers has made me bold to speak with some authority on what my eyes and fingers have learned about the technical aspect of ancient armour and weapons...’[57]

Laking, who was by his own admission a connoisseur and not a scholar, was keenly aware of his own deficiencies as a researcher and sought to compensate for them by making great use of the work of colleges who were more formidable researchers into the documentary aspect of medieval arms and armour. Unlike the authors of the several handbooks on arms and armour which had appeared around the turn of the century Laking was very well informed as to current research in the field, and although he acknowledged his debt to Meyrick, he did not base his work so heavily upon the conclusions that were reached in the early nineteenth century. ‘If I owe much of my knowledge of this subject to the pioneers of armour learning,’ he writes, ‘I must confess a still greater obligation to present-day authorities: again and again I have availed myself of the fruits of their research, but never, I trust, without full acknowledgement.’[58] Laking’s list of contemporary authorities is indeed impressive, including as it does most of the British writers on the subject then living, including Baron de Cosson, the late Sir William St. John Hope, The Viscount Dillon, Mr. Charles Ffoulkes, Mr. Oswald Barron, Mr. S. J. Whawell, Mr. Felix Joubert (collector), Sir Farnham Burke, K.C.V.V., C.B. Garter King of Arms (collector) and Cripps-Day. The greatest strength of Laking’s Record, however, lay not so much in the text but in the hundreds of photographs of arms and armour which it contained. S. J. Camp, who examined the work in a lengthy series of reviews for the Burlington Magazine, writes ‘...Sir Guy Laking’s book will be one not only welcome but indispensable to the student and collector. It is the first attempt on a large scale to give a general view of the development of arms and armour since photographic reproduction revolutionised book illustration, and it consequently surpasses in scope anything which has yet appeared.’[59] Laking’s expertise, derived as it was from years of handling armours, was very much of the ‘touch and feel’ variety, but as a protégé of de Cosson he followed the methods laid down by his mentor in Helmets and Mail when examining a piece. De Cosson, who provided a lengthy introduction to the Record writes;

‘Always addicted to the study of natural science, it had seemed to me that armour and arms should be examined in the same manner in which the scientist proceeds. How does the naturalist, the geologist, the palaeontologist pursue his studies, but by collecting the greatest possible number of specimens and then, by a careful collation of this material, he is enabled to evolve a logical and scientific theory and history of the objects which form his study. It is for this reason that I have insisted upon the value of a really extensive picture book, although a minute examination of the greatest possible number of real examples must always be the basis of a truly critical and profound knowledge of ancient armour and weapons. The number of students in Europe who follow this course is increasing, and I doubt not that the present book will do much to interest the reading public at large in the subject.’[60]

The Record of European Armour is the most substantial work ever written on the subject in the English language, comprising as it does 1691 pages and 1572 illustrations. The overall organisation of the work was a compromise between the strictly chronological approach of Meyrick and Hewitt, and the encyclopaedic organisation by type of Grose and de Cosson. The first book is largely given over to a chronological history of arms and armour from 1000 to 1500, while the remainder of the work is divided into chapters which deal with specific types of weapons and armour, which themselves are arranged in a roughly chronological fashion. A full table of contents of the work is as follows;

Chapter I:

General History of Armour and Arms, Prior to the Norman Conquest,

A.D. 1000-1070, pp. 1-31.

Chapter II: Early Norman Period. General History of Armour and

Arms A.D. 1070-1100, pp. 32-65.

Chapter III: General History of Armour, Arms and Accoutrements,

A.D. 1100-1320, pp. 66-107.

Chapter IV: General History of Armour and Arms, A.D. 1200-1300,

pp. 108-144.

Chapter V: General History of Armour and Arms, A.D. 1300-1400,

pp. 145-159.

Chapter VI: General History of Armour, A.D. 1400-1500, pp. 160-185.

Chapter VII: General History of Armour, A.D. 1400-1500, pp. 186-224.

Chapter VIII: The Bascinet Head-Piece from the Early Years of

the XIIIth Century to the Close of the XVth Century, pp. 225-265.

Chapter IX: The Helm from the Early Years of the XIIIth Century

to the End of the XIVth Century, pp. 266-286.

Chapter X: The Salade Head-Piece, pp. 1-56.

Chapter XI: The Head-Piece called the Chapel-de-Fer or

Chapawe, pp. 57-71.

Chapter XII: The Armet Head-Piece from the early years of the

XVth Century to the Commencement of the Next Century, pp. 71-98.

Chapter XIII: The Helm of the XVth Century, pp. 99-167.

Chapter XIV: Chain Mail and Interlined Textile Defences, pp.

167-203.

Chapter XV: The Gauntlet, pp. 203-223.

Chapter XVI: The True Shield of the XVth Century, pp. 223-249.

Chapter XVII: The Sword of the XVth Century, pp. 250-330.

Chapter XVIII: Swords of Ceremony in England, pp. 331-347.

Chapter XIX: Daggers, pp. 1-80.

Chapter XX: Hafted Weapons in General use from the Middle of

the XIVth Century to the Commencement of the XVIth Century, pp.

81-126.

Chapter XXI: The Crossbow, pp. 127-146. Chapter XXII: Horse Armour,

the Bit, Saddle and Spur from the Beginning of the XIVth Century

to the end of the XVIIth Century, pp. 147-208.

Chapter XXIII: The Dawn of the XVIth Century - The Tower of London

Armoury, pp. 209-239.

Chapter XXIV: The Maximilian School, pp. 240-271.

Chapter XXV: Armour of a Type now Vaguely Termed Landsknecht

and XVIth Century Armour under Classical Influence, pp. 272-301.

Chapter XXVI: Armour Termed ‘Spanish,’ pp. 302-329.

Chapter XXVII: The School of Lucio Picinino, pp. 330-341.

Chapter XXVIII: Armour Termed ‘French,’ pp. 342-358.

Chapter XXIX: English Armour of what we now term the Greenwich

school-armour made for England, pp. 1-76.

Chapter XXX: the latest XVIth century suits of continental make

- decadent armour commonly known as ‘Pisan,’ pp. 77-87.

Chapter XXXI: Close Helmets of the XVIth Century, pp. 87-124.

Chapter XXXII: The burgonet or open Casque, pp. 125-192.

Chapter XXXIII: Morions and Cabassets, pp. 193-217.

Chapter XXXIV: Italian, German and French Pageant Shields, pp.

218-259.

Chapter XXXV: The Sword and Rapier of the XVIth Century, pp.

260-329.

Chapter XXXVI: Hafted Weapons of the XVIth and XVIIth Centuries,

pp. 330-353.

Chapter XXXVII: The Dawn of the XVIIth Century, pp. 1-58.

Chapter XXXVIII: XVIIth Century Swords and Rapiers, pp. 59-110.

Appendix I: Notes on Forgeries, pp. 111-148

Appendix II: On Armour Preserved in English Churches, by Francis

Henry Cripps-Day, pp. 149-274

Appendix III: General Bibliography, by Francis Henry Cripps-Day,

pp. 257-304.

Index to the complete work, pp. 305-383

The first volume of Laking’s Record comprised 286 pages of text and 329 plates. The first seven chapters provide a general chronological survey of arms and weapons from just prior to the Norman Conquest to 1500. Although Laking was primarily a connoisseur of armour, his wide knowledge of medieval art ensured that iconographic evidence was given its due. In addition to the many photographs of armour and weapons, tapestries, paintings and woodcuts are also reproduced in the Record . The reviewer of the work in the Connoisseur wrote of the first volume;

‘The earlier portion of the period covered presents many difficulties to the conscientious historian; not many weapons of the time have survived, and only a few pieces of the defensive accoutrements of either knights or men-at-arms...To fill in the ellipses posterior to this time, it is necessary to gather data from early drawings, pictures, embroideries, and sculptured figures on tombs. In this Sir Guy’s artistic and archaeological knowledge has stood him in good stead, and he has gathered illustrations from a wide variety of sources to supplement the photographic reproductions of actual weapons and pieces of armour.’[61]

The question of mail armour is addressed in the first book of the Record, and Laking comes down firmly on the side of Hewitt in the debate over the construction of the early forms of this armour, writing;

‘But here we are confronted by the difficulty with which all students of the history of armour have to contend; how were the old English mail-shirts wrought? Was it a garment of leather on which rings of metal were sewn at regular intervals, in varying degrees of closeness according to the quality of the shirt, or was the hauberk or ring-byrnie a true shirt of inter-linked chain-mail? We incline to the theory that the Anglo-Saxon hauberk was of chain-mail; for without doubt true shirts of mail of the Viking type have been discovered both at Vimose and Thorsberg.’[62]

Figure 6.5: 'From the Bayeux Needlework. Four conventional ways of what the author believes to be the ordinary hauberks of linked chain mail.' Figure 45 from Laking's Record of European Armour, vol. I.

Laking accepted Hewitt’s conclusion that the variety of patterns medieval artists used upon armoured figures was indicative of mail armour, and not evidence of a variety of different types of armour, as Meyrick had proposed. The reviewer of the first volume of the work for the Archaeological Journal, concurs with Laking’s assessment of mail, writing ‘Any one who has tried to draw mail will appreciate the difficulty which we venture to think has been the cause of so much confusion in arriving at what was really worn.’[63] The evidence from archaeology had at last put an end to the debate that had been raging in the antiquarian world since Meyrick’s theories of early body armour were first challenged. Such terms as ‘tegulated,’ ‘mascled,’ and ‘telliced’ mail were at last rendered obsolete, a century after Meyrick had first put them forth in the pages of Archaeologia.

The second volume of the Record of European Armour, comprising 347 pages and 394 plates, abandons the strictly chronological approach of the first seven chapters altogether and examines several different types of helmets, as well as gauntlets, ceremonial swords and mail and textile armours from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The forsaking of the strictly chronological approach is explained by Laking in the first volume;

‘In tracing the evolution of armour and weapons the greatest difficulty we have to contend with is in keeping the changes that continually took place sufficiently clear before our reader, to enable him to picture to himself a knight fully equipped at, or near, any particular date that he may desire... Unfortunately, without any thought or feeling for the student of armour...the knight proceeded in his arbitrary way to alter the fashion of his head protection in one period, of his body armour in another, and of his leg defences and of his offensive weapons in even a third and fourth, allowing the fashions in the case of every piece of armament each to overlap one another in a most perplexing manner. Therefore, it is impossible do otherwise than to take our subject in general periods most suitable for our purpose, and to trace the changes in each detail of his equipment separately, retracing our steps as is obligatory to pick up the story of each.’[64]

These chapters are all characterised by the sort of in-depth analysis of specimens that one would expect of a student of de Cosson’s. Pieces are described in minute detail, and often illustrated with a wealth of examples, both from contemporary artwork and from arms and armour collections across the world. In the thirteenth chapter, ‘The Helm of the 15th Century,’ Camp commends Laking for managing to acquire ‘...reproductions of well-nigh every known example of importance whether in private or public possession.’[65]

The third volume, of 347 pages and 394 illustrations, comprises chapters 19-28, and covers a diverse range of topics including daggers, horse armour, crossbows, the history of the Tower of London armoury and several ‘schools’ of armour making. In this volume particularly one sees the influence of Laking’s many years in the sales rooms, particularly with regard to his classification of armour into rather vague and unsatisfactory groups based more upon ‘armour jargon’ and shop talk than on any rational basis. The very title of chapter XXV, ‘Armour of a Type now Vaguely Termed Landsknecht and XVIth Century Armour under Classical Influence,’ clearly exhibits the weakness of his scheme. ‘A more scientific classification’ writes Camp ‘would have been a boon to students who must clarify their vocabulary if they are to clarify their ideas.’[66] Laking’s classifications, based more upon aesthetics than upon documentary evidence, is in contrast to the Greenwich school of armour which is discussed in chapter XXIX in the fourth volume. This class is based upon the careful study of Viscount Dillon into documentary sources, particularly the Jacobe MS., and provides a much more rational and useful framework for investigation. Laking is aware of the difficulties of classification, and describes his ‘...constant struggle with the difficulty of adhering with absolute rigidity to our twofold system of classification - that according to form, and that according to provenance.’[67] Although the classes he delineates as ‘French,’ ‘Spanish,’ and ‘Landsknecht’ are of little use, his discussion of the ‘Maximilian School’ and the ‘School of Lucio Picinino’ are based upon firmer documentary sources and are still recognised today as valid categories of armour.

The fourth volume, consisting of 353 pages and 324 illustrations, is, like the third volume, a miscellany of topics which are arranged in a more-or-less chronological fashion. The first chapter of the fourth volume, ‘English Armour of what we now term the Greenwich school-armour made for England,’ provides a good example of Laking’s use of up-to-date research from contemporary experts, as it is based to a very large degree upon Viscount Dillon’s work on the Jacobe MS. Likewise, his discussions of the various forms of helmet also make use to a great degree of the work of Baron de Cosson, whose help the author gratefully acknowledges.

The fifth and final volume, comprising 383 pages and 148 illustrations, contains the final two chapters of the main body of the work and three important appendices. In appendix I Laking discusses forgeries, while the other two, which were written by the work’s editor F. H. Cripps-Day, consisted of a survey of armour preserved in English Churches and a general bibliography respectively. On the sensitive issue of forgeries, Laking followed the example set by de Cosson’s in Helmets and Mail and devoted considerable attention to discussing and exposing several examples of spurious armour, although as he admits in the author’s preface ‘...in that section of this work I know that I move over very thin ice.’ ‘I could easily have filled the chapter with illustrations and descriptions of the famous forgeries of armour and weapons which are contained in English collections,’ he continued, ‘but I am not eager for controversy...’[68] His general comments on forgeries in armour mirror those of de Cosson, as he pays considerable attention to details of form and function;

‘In the case of almost every individual piece belonging to this school of forgeries, whether designed for the head or for body wear, the first thing that strikes the eye is the impossibility of its actual use...Most of the plates of which it is constructed appear to have been made out of pieces of worn-out stove-piping or from rolled sheet-iron, in which...the peculiar markings left by the rollers on the surface are distinctly traceable. In nearly every instance the metal has never been polished, with the result that the remains of the black oxide appears in specks all over it...the pieces are clumsily fashioned, wretchedly constructed, and executed with the least possible trouble. The rivets are often not more than round-headed nails; the edges of the plates seem to have been cut with shears; while such attempts at decoration as are found might have been made by a savage from Central Africa.’[69]

This appendix is one of the most interesting parts of the work and provides one of the best general surveys of nineteenth and early twentieth-century forgeries. Laking’s long experience in the antiquities trade made him, as Camp notes, the most qualified man to write of this subject (more qualified that even he suspected, if Duveen is to be believed).[70] Considering Laking’s work from the point of view of the collector this appendix is an invaluable aid to spotting fraudulent pieces at the sales room.

Cripps-Day’s contribution to Laking’s work included an essay and survey of English church armour, relics from the days when armour and weaponry were hung as funeral achievements. This was added as an appendix to the last volume of the Record, and was introduced in the following manner;

‘I hope that the notes which I have now collected may serve as a preliminary survey of which others may hereafter add to, correct, and amplify.. The late Sir Guy Laking described a considerable number of church helmets in the previous four volumes of work, and to these descriptions I have referred; but I have felt that his "History of European Armour and Arms" ought to include a complete an account as possible of these national treasures preserved in our churches, in view of the fact that a large proportion of the helmets are genuine pieces, many of them being fine examples and almost certainly the work of English armourers.’[71]

An additional goal of this appendix was to document as many of the armours in churches as possible in order to discourage theft. ‘Mr. Cripps-Day will have done no mean service to the students of armour,’ writes Camp ‘as to the dead, if the further pilfering of English churches is rendered more hazardous and difficult.’[72] The editor’s final service to Laking’s Record was in the addition of a comprehensive bibliography of arms and armour works and a complete index.

Laking’s methodology was a synthesis of those used by Meyrick and de Cosson. While he followed the general outline of the chronological approach that Meyrick pioneered in the first seven chapters of the work, he abandoned this plan in the remaining chapters and dealt with the various forms of armour and weapon by class, in a manner not dissimilar to de Cosson’s discussion of helms in Helmets and Mail. Laking commented upon the difference between the latter philosophy and that used by Meyrick, noting;

‘It is a fact worthy of comment that, despite the careful research and close observation which distinguished every page of his great work, Sir Samuel Meyrick never appears to have attempted any scientific classification by which armour or weapons could be grouped together under heads according to their types; in place of this arrangement he treated each piece individually.’[73]

Laking’s compromise was to some extent necessitated by the size of the work, as it would have been extremely difficult for him to present the hundreds of examples which he had collected in a purely chronological manner without losing sight of the developments that were occurring within each type of armour or weapon. By providing a chronological framework in the first volume he was able to then concentrate upon each type of armour in turn, allowing a great number of similar specimens to be compared side by side, the better to show the subtle changes that occurred over time. Although this approach led to a considerable amount of overlapping chapters, it does, as Camp points out, allow for greater continuity and concentration when discussing a particular type of weapon or armour. Another of Laking’s goals in the chapters of the work that dealt with specific types of armour and weaponry was, according to Cripps-Day, to establish a system of armour and weapon classifications based upon ‘schools’ of style, a system borrowed from the art historian.[74] Yet in carrying out this plan he perhaps put too much faith in his own abilities to distinguish subtle changes in the form and decoration of the pieces and not enough in other, more objective, forms of evidence. It is, for instance, remarkable that Laking paid so little attention to armourer’s marks, which are as significant to the question of the origin of any given armour and weapon as is an artist’s signature to a painting or a sculpture.

For those collectors who were disappointed by the scarcity of illustrations of armour in Hewitt’s volumes, Laking’s Record of European Armour more than satisfied their desires. Over a thousand photographs, line drawings and diagrams, drawn from collections across the world made these volumes an invaluable reference work to both the student and the collector. Laking had been soliciting collecting photographs of armour and weapons from collections across the world of for many years, and his persistence was rewarded by a very broad sample of European weapons and armour.[75] The photographic acknowledgements in the author’s preface mentions a great number of collections and institutions including the Trustees of the British Museum, the National Gallery, the Board of Education (Victoria and Albert Museum), the Curator of the Tower of London Armoury, the Directors of the Royal Scottish Museum and the Royal united Service Institution, the College of Arms, the Society of Antiquaries of London, the Royal Archaeological Institute of Great Britain, the Committee of the Royal Artillery Institution, the Royal Regiment of Artillery, the Burlington Fine Arts Club, the Dean and Chapter of the Abbey Church of Westminster, the Dean and Chapter of the Cathedral Church of Canterbury, the Director of the Belfast Museum, the Curator of the City Museum, Norwich, the Librarian of New College, Oxford, the Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, the Curator of the Public Museum, Sheffield, the Corporations of the Cities of London, Bristol, Coventry, Hull, Lincoln, Newcastle and York, the Curator of Armour of the Metropolitan Museum of New York, Director of the Musée du Louvre, Paris, the Director of the Musée d’ Artillerie, Paris, the Director of the Bibliothéque Nationale, Paris; he also notes the Porte de Hal, Brussels, the Bargello, Uffizi and Stibbert of Florence, Museums of Bologna, Turin, the Arsenal at Venice and the Royal Armoury at Madrid.[76]

While previous works that had been based upon depictions of actual armour and weapons, such as Meyrick and Skelton’s Engraved Illustrations and Brett’s Pictorial and Descriptive Record, were exclusively comprised of illustrations from a single collection, Laking was able to provide the reader with an account of European arms and armour drawn from the greatest collections across the world, many of which had never been illustrated, much less photographed, before. Photography revolutionised the study of arms and armour, and Laking was the first writer to take advantage of it on a large scale.

The use of photographs explains the great predominance of evidence drawn from artefacts that is apparent in all chapters of the Record of European Armour, as is shown on graph 5. Laking’s work is based very much on visual evidence, drawn both from photographs and drawings of the armour and weapons, and from medieval iconography. Indeed, in some chapters there are scarcely any references made to any other form of evidence, such as that from documentation, and in most chapters iconography and photographs supply at least a third of the total references made. The photographs not only make up the bulk of the references, but they also make up the bulk of the work itself with many large photographs taking the place of text. Laking’s goal of creating a ‘picture book with commentary’ was largely realised, although he was perhaps too modest in the appraisal of the finished work. While it did not break as much new ground as did Hewitt’s Ancient Armour and Weapons or Baron de Cosson and Burges’s Helmets and Mail, the Record of European Armour did offer the reader with a good summary of the current knowledge in the field, as well as calling greater attention to what could be called the technologically decadent but decoratively superior armours of the late sixteenth and the seventeenth centuries.

In addition to the many photographs of weapons and armour, the Record is replete with numerous photographs of medieval and renaissance artwork depicting arms and armour, as well as a great number of line drawings (figures 6.6, 6.7). Although many of the drawings were done by the author’s own hand, in some cases Laking reproduces line-drawings from other publications including Viollet-le-Duc’s Dictionnaire, although these are not always to his advantage. Camp, in his review of the work in the Burlington Magazine, criticised Laking’s use of reconstructions in much the same way that Hewitt wrote of Meyrick’s reconstruction in the Critical Inquiry. ‘Interesting thought these reconstructions are to the theatrical costumier, and as an aid to the imagination,’ he writes, ‘they are not infrequently mistaken for facts, and it would have been better to disassociate them from a serious work of this kind.’[77] Over half a century earlier, John Hewitt had insisted upon the necessity of reproducing the source material ‘line for line and mark for mark, so that, if the author's notions are aberrant, the reader has the means of rectification in his own hands.’[78] In the age of photography this dictum truly came into its own, and Laking’s work is strongest when it draws its arguments from the hard evidence that they provide rather than from the author’s interpretations.

The Record received very good reviews in the art journals, the popular press and the archaeological publications, although one does often get the impression that the author’s untimely death added a degree of sympathy to the reviews that would not otherwise have been the case. Ffoulkes in particular, who proclaimed in the Times that ‘...[Laking’s] great work will live as the standard work on Arms and Armour for all nations and for all time,’ seems to have been carried away by the emotion of moment.[79] A more sober evaluation of the work appeared in the pages of the Connoisseur, whose reviewer described the Record as ‘...a learned work, but also a fascinating one, which can be read with pleasure by everyone interested in the history of war, as well as the collector of warlike implements.’[80] The reviewer of Laking’s work in Archaeological Journal writes;

‘[Meyrick’s] researches have been supplemented by Lord Dillon, the Baron de Cosson and others, and in the present work Sir Guy Laking seeks to consolidate the labours of his predecessors, adding his own extensive knowledge and perception, together with the experience of many friends, and illuminating his material by a copious wealth of illustration.’[81]

More recent writers such as Claude Blair have also called attention to the fact that the Record was in many ways a compilation of the work of many early twentieth-century writers.[82] Laking’s work thus not only brought a great many armours to the attention of a wider audience through photography, but it also served to bring the work of many specialists in the field to the attention of the reader.

Despite the sometimes immoderate praise most reviewers did acknowledge the fact that Laking’s work suffered from a number of flaws, most of which stemmed from the author’s lack of a scholarly background. The major flaws of the Record are summed up concisely by Camp in his review for the Burlington Magazine, where he writes;

‘Where an author has given so much it may seem ungracious to make reservations, but in view of the unmeasured praise which has been given, and the claim even for finality that has been set up [in reference to Ffoulkes’ review of the work in the Times ], it is necessary to say a word by way of criticism, and that can best be done by describing the difficulty with which the reader of this book is constantly faced...[The reader] knows that the author was familiar with his subject to a degree perhaps unequalled: no living man probably had seen or handled so many specimens. From this rich experience he had won a high degree of certainty and authority in estimating the authenticity and quality of any piece brought before him, and could rapidly assign it to its place (or thereabouts) whether of date or provenance...But with this quickness of intuition went a certain impatience on Sir Guy Laking’s part in making good his conviction for others, and in supplying a scholarly apparatus by which they might be tested...The result is that those who come after him must verify and test these foundations for themselves, and the general vagueness of his references, or their omission altogether, renders it necessary first to identify his authorities, and behind these to review the facts on which the opinions referred to were based.’[83]

Figure 6.7: 'From Hans Burgkmair's "Triumph of Maximilian," Figure 399 from Laking's Record of European Armour

It is interesting to note how such criticism could equally be levelled at Meyrick. The Critical Inquiry suffered from many of the same problems as did Laking’s Record and for many of the same reasons. In both cases the authors were extremely knowledgeable about their subject and often prone to make assumptions that were, while perhaps reasonable to the experienced connoisseur, obscure to the average reader. And like Meyrick, Laking often did not make a distinction between a strongly held opinion and a fact that was backed by evidence and argument. Sir James Mann, Ffoulkes’ successor at the Tower of London remarked that ‘Laking made no claim to scholarship. His attributions were founded on the current talk of collectors and the sale room, and he seldom checked the assumptions of his day by reference to evidence of a more specific nature. He had a tendency to describe as French anything that was elegant, and Italian anything that was rich.’[84] While Laking would often expound at length over the subtle aspects of form and decoration of a piece, he would often overlook more objective clues to an items origin. Camp notes in his Burlington Magazine review that ‘The few references which Sir Guy Laking makes to armourers’ marks, and the absence of a single reproduction of them, do suggest that he was inclined to under-value the evidence which they afford.’[85] Laking’s methods were those of an art critic, not an archaeologist, and his work often suffered as a result.

Laking’s lack of scholarly method is contrasted with that of his mentor, particularly in the first volume of the work. Camp notes that while de Cosson provided 148 footnotes in his 27 page introduction, Laking supplied only one footnote in the 286 pages of text that followed. Camp also calls attention to the vagueness of many of Laking’s statements with the following examples drawn from the first volume of the work; ‘It has been suggested...’ (p. 16), ‘This theory, brought forward by a very eminent authority...’ (p. 18), ‘Experts on architectural ornament assign...’ (p. 21), ‘There has been of late a controversy of experts...’ (p. 49). None of these statements is backed with any precise reference making independent verification by the reader almost impossible. The following four volumes of the Record were to benefit from the attention of Cripps-Day who edited the work and did his best to provide references to the assertions of the author, who he noted ‘... was not a literary man and was no great reader.’[86] In the foreword to the second volume, he writes;

‘In writing his book Sir Guy Laking did not think it necessary to give precise references to the authorities from which he quoted; moreover, his authorities were often opinions of experts expressed to him viva voce. If I have succeeded in verifying most of the references to books, it has been mainly due to the help of Mr. Charles Beard, who possesses a wide and accurate acquaintance with the literature of Arms and Armour.’[87]

Again, one sees parallels with the Critical Inquiry. Cripps-Day seems to have fulfilled a similar role with regards to the Record as was played by Albert Way with regards to the second edition of the Critical Inquiry. As will be recalled, Way helped to edit this volume and ‘was at considerable pains to verify the author’s documents and quotations, in which he had not bestowed sufficient care.’[88] While Laking’s scholarship may have been imperfect and many of his conclusions often based upon intuition rather than sound reasoning, there can be little doubt that by bringing together such a vast number of photographs of arms and armour from collections around the world, as well as drawing upon the work of many contemporary writers on the subject, his work would prove to be a great benefit for the researcher and the collector.

Despite its many shortcomings, there were areas in which the Record of European Armour and Arms did break new ground in the study of arms and armour, particularly with regards to the armour and weaponry from the later periods which had only been briefly discussed by Meyrick and Hewitt. Laking’s attention to the later periods reflects his experience in the sale-room where the often highly decorated armours of the sixteenth and seventeenth century were highly sought. In a time when fine armour and weapons were beginning to be recognised as objects of art, rather than simply the practical tools of war, it was inevitable that the armours from the later periods would have great appeal, as often times these armours were exquisitely decorated with embossing, etching, gilding and enamels. Indeed, many of the ‘parade harnesses’ from the close of the age of armour were so elaborately decorate that they were useless for defence, and could more properly be considered elaborate items of male jewellery, intended purely for display. On such harnesses, the practical considerations of the glancing surface and robust construction were abandoned in favour of extravagant decoration which gave the artist free reign.

The Record of European Armour and Arms was an important milestone in the historiography of medieval arms and armour, and one that largely satisfied the collectors, scholars and reviewers of the time. ‘Sir Guy Laking has, indeed, covered his subject with exemplary thoroughness’ wrote the reviewer for Connoisseur, ‘...It is a work which no serious student of mediaeval European history can afford to ignore, while to everyone interested in armour, either as a collector or custodian, the work will be indispensable.’[89] By combining and updating the work of earlier writers with that of his contemporaries, Laking created a work that provided a fairly comprehensive survey of arms and armour study and largely satisfied the desire amongst students and collectors of arms for ‘a new Critical Inquiry.’

The Record of European Armour was the last of the great antiquarian works on the subject, and one of the last of the works of the old school of amateur d’armes. Despite its shortcomings, Laking’s life work is an important reference work, and a monument to the ‘age of the connoisseur,’ one of the most interesting and productive phases of the historiography of medieval arms and armour. ‘Many in the future will write of Armour,’ wrote Cripps-Day, ‘but never, I am convinced, will they approach their subject without turning the leaves of Sir Guy Laking’s book to find therein guidance, knowledge, illumination, and something too, I trust, of the spirit of the man, and of his great love and devotion to his subject.’[90]